LATEST NEWS

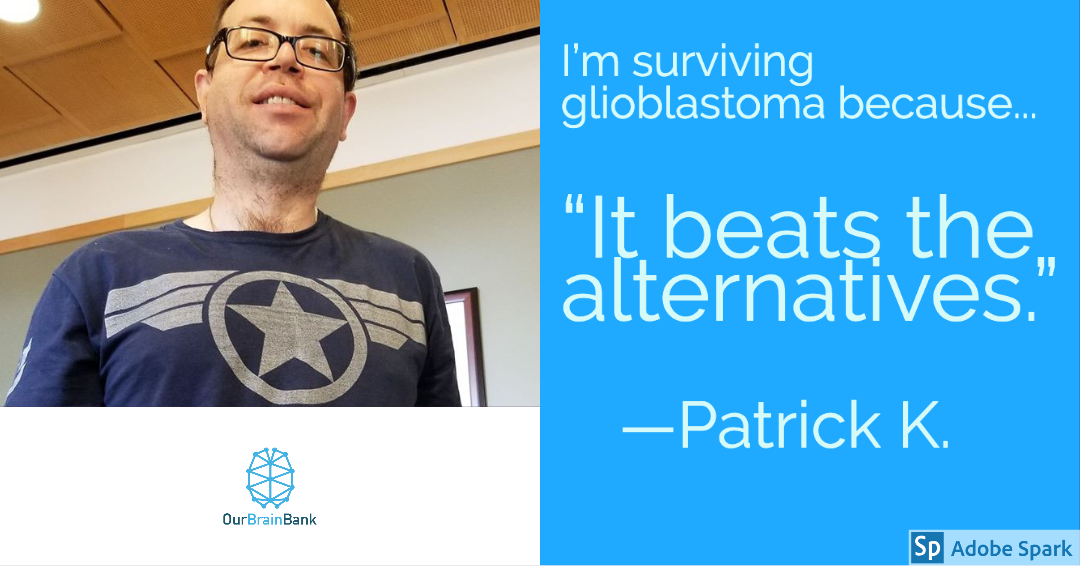

Patrick, a long-term GBM survivor.

NEWS September 2023

Patrick writes with intelligence and dark humor about what’s like living with GBM.

My GBM Story: Patrick Koske-McBride

Patrick has a way with words. After an education in biomedical science, with a focus on the genetics of neurodegenerative disease, and a stint in medical school, Patrick, from California, turned to writing, and maintains an active blog, where he muses on everything from science and medicine to movies and pop culture.

Ironically, prior to his GBM diagnosis, he was briefly employed by a biotech investment consultant as a market analyst for GBM treatments.

He describes the first brain surgery he received — at age 17, to remove a neurocytoma tumor — as “sand-blasting a soup-cracker.”

“It put my right cerebral hemisphere at three standard deviations below normal for electrical activity. Electrical activity in the brain is correlated with neuronal activity, so, in English, I was far dumber than I was used to.”

Ask him to describe cancer, and his analogies range from Mad Max movie references:

“If you’re the last radioactive cannibal in your timezone, all those abandoned supermarkets, muscle cars, and elk are yours for the taking”

To music:

“Our bodies are made up of a symphony of cells that play by very specific, coordinated rules to perform a complex piece of music, divide a limited number of times, and then die. In this analogy, your genetic code is like the sheet music that everyone follows, and your immune system is like the conductor — it scowls at the timpani when it gets too loud or goes too fast.”

“To coordinate cellular activity so that you don’t get a rogue group of trumpets, guitarists, and trombones forming a mariachi band on the opening night of Nutcracker, your genetic code has two types of genes involved: proto-onco genes, which cause cells to grow and divide; and tumor-suppressor genes, which deactivate the proto-onco genes. When you have a tumor suppressor gene permanently deactivated and a proto-oncogene activated, you have cancer.”

“That’s it. Just two mutations in a single cell, and your body is no longer a symphony, it’s post-apocalypse Australia.”

“If only we could avoid all carcinogens. Except we can’t. Sunlight and oxygen are carcinogenic. Luckily, our bodies are really good at detecting and repairing this damage.”

“My long-suffering immunology prof once said he calculated that every cell in your body gets over 10,000 genetic ‘challenges’ each day, but only two or three dozen permanent mutations in your entire body per year,” Patrick says. “Once that single cell is cancerous, it can remain dormant and undetected by your immune system. When several cancerous cells get together, however, tumors can form.”

Patrick has had three brain tumors. His most recent diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme came on November 10, 2017. He received standard of care (surgical resection/biopsy, radiation, and chemo) with an repurposed drug (developed for multiple myeloma) Marizomib, for the GBM.

He believes personalized medicine — physicians adapting their treatment and approach to you in a way that’s as aggressive and effective as possible, while keeping you alive and maintaining what you’d consider an acceptable quality of life — is the way forward when it comes to cancer care.

“Personalized medicine is really important with GBM because this isn’t some sort of monolithic disease, but dozens — possibly hundreds — of different, distinct subtypes of brain cancer that have only a common progenitor cell,” he says.

His advice for newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients?

Become a self-advocate and set the pace and tone for your doctors from Day 1.

Do not translate the term “inoperable” as “abandon all hope.” Take it to mean “We don’t have the technology or proficiency to surgically treat it/biopsy it HERE,” and seek a second opinion elsewhere.

Your goal shouldn’t be to find a magic-flower-in-the-Andes cure; it should be to treat this as an ongoing, dangerous chronic disease, like heart disease, thyroid disease, mental illness, or diabetes. Those patients don’t mope about their condition being incurable, they just manage as best they can so they can get the next treatment.

On the OurBrainBank app

(Note: the OurBrainBank pilot study using this app closed in 2021)

“OurBrainBank was extremely helpful in keeping track of treatment side-effects,” he said. “As of April 2020, I’m two years post-diagnosis, 25 months with NED (No Evidence of Disease). I’m still recovering from treatment (which required weekly infusions for a year; Marizomib is not for the faint of heart), but I also still use the Our Brain Bank app frequently to track fatigue and sleep issues.”

Patrick on Jessica Morris, founder of OurBrainBank

“Cancer is tremendously isolating… But your psychological suffering does diminish, somewhat, when you stop looking to the surface dwellers for comfort, and start looking to your fellow sea monsters.

The moment I began to see a glimmer of light from my fellow sea monsters — that they believed in me, even if no one else did — came from the incredible Jessica Morris of Our Brain Bank.

On a live chat, Ms. Morris enthusiastically greeted everyone — “Hello, Jamie! Hello, Patrick!” That was the moment. It wasn’t a big thing; she was just pleasantly acknowledging me.

One tiny little glimmer of unremarkable kindness, stacked up against an ocean of ignominious agonies and suffering. It made a difference.

Which is a very, long, roundabout way of saying, thank you so much, Jessica.”

Read Patrick’s writings on cancer, survivorship, Barbenheimer, and other topics on Medium.

Interview conducted in 2020