PERSONAL STORIES

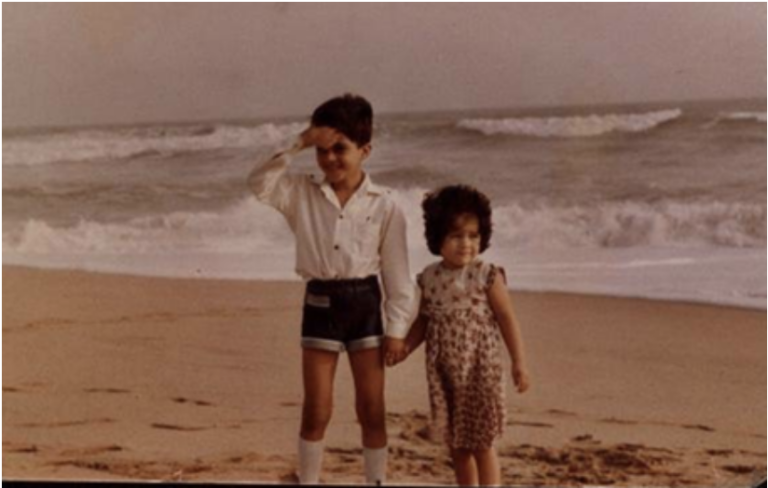

Yaron Butterfield’s Story.

NEWS 21 July 2022

![YaronButterfield1[1]](https://www.ourbrainbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/YaronButterfield11.jpg)

Yaron was working as a genomics researcher, tasked with sequencing the SARS genome in April 2003. Ten months later, he collapsed and his life changed forever.

I collapsed in February 2004 and was transferred to the main hospital in Vancouver. It was a Monday morning and it wasn’t until the middle of Wednesday that I came out of a drug-induced state. My brother was there and I actually told him to call my boss and tell him I’d be a bit late for work. It turned out I wouldn’t be back for three years. An MRI scan showed something there, but about a week later, after a biopsy, I got the actual diagnosis — they zeroed in and saw glioblastoma.

Back then it was normal to do radiation followed by chemo, but a physician had come up with the idea of doing radiation and chemotherapy together, and he’d published a study that showed there was benefit to combining them, so I got in right at the start when they were still looking into that as a protocol.

My neuro-oncologist was amazing. Nobody liked him when they first met him because he was a bit awkward and never smiled. I think it’s because brain cancer is so hard to treat and so many people don’t make it. It’s got to be hard for the physician. But I noticed over the years, as it became obvious I was beating it, that he would smile, and we had great chats. The main thing was, he was probably the best neuro-oncologist in Canada.

He made sure he knew the best way for me to be treated, which meant, in my case, I probably should not have surgery because the tumour was quite deep in the brain. I don’t know if they were joking but they said they knew I was a cancer researcher and they didn’t want to do anything in my brain that might affect my abilities to do complicated research.

He actually even said we should see what others think so he sent my pathology slides to Sloan Kettering, Johns Hopkins, and another hospital in Toronto. He was completely okay with getting a second opinion. Two of the three hospitals agreed with the plan he had for me; only the one suggested surgery — because that’s what they typically did.

So we decided not to do surgery. In the brain cancer world, because I’m starting to get known as a long-term survivor, a lot of people are surprised that I’ve survived this long, but that I actually never had surgery.

I also didn’t quite complete the combined Stupp Protocol [since 2005 the Stupp Protocol has been the standard of care for treating glioblastoma and consists of radiotherapy and chemotherapy with temozolomide.] because I was very sensitive to chemotherapy. It affected my blood counts and I actually had to stop it after three weeks.

Meanwhile, I decided to go on a dating profile! This was before I even got the results of the treatment. Maybe the reality hadn’t quite hit me — I was sort of in la-la land. The truth is that before the diagnosis my career was going really well and I thought maybe in a year or two I’d go and get my PhD. I’d just broken up with a long-term girlfriend and I thought I had all the time in the world to meet new people. Then, after the cancer diagnosis, there was this realisation that I’m not going to live forever — who knows how long I’ll live — so I thought I should get a family, have get kids, and that’s why I went on a dating website and I met someone. On our second date I told her about my diagnosis. I said you can get up and leave and I’ll understand, or you can have a meal with me and then get up and leave. Instead, we started dating.

That summer I got the results of my treatment and it worked. Five months later I ended up running a full marathon in Iceland — but I may have been pushing my body too much because a month or two after that, the cancer came back.

Usually when you get chemotherapy for GBM, it’ll kill a whole bunch of cells and the tumour shrinks, but it usually does not go away completely, and the reason is you’re going to have some cells that are resistant to TMZ. Even if the new tumour is the same size and the same shape as the original tumour, even if it looks the same in the MRI, it is actually genetically quite different than the first tumour. And this usually becomes a bigger tumour of duplicating cells that are resistant to TMZ. That’s why TMZ rarely works a second time. So they put me on a clinical trial — of a drug that had been successful with another type of cancer —but it was an absolute disaster.

I was on this clinical trial when I got married. The alarm on my watch to tell me to take the drug went off during our wedding ceremony. A further MRI showed the tumour had doubled in size, so my neuro-oncologist thought: what do we do now? He felt we should try TMZ again because I hadn’t completed the course last time.

I had the chemo the first week of each month and I remember that with each month it seemed to affect me more. But by August the tumour had shrunk— to the point where it was almost gone. At that point, they suggested I have an MRI every three months. Three months later it showed no change at all. If I had an MRI today you could probably still locate where the tumour was, but my doctor says what you’re seeing is probably just scar tissue, not the tumour.

After my diagnosis, I had searched for any sort of books with stories of survivors and I couldn’t find any. I wish there had been. I remember my neurosurgeon Dr. Toyota — the one who did the biopsy — had told me it’s a tough disease. But to show my prognosis he drew a chart on a board and drew a line going down showing over months and months how survivorship drops completely. The line didn’t quite come all the way down to the x-axis. He told me there were long-term survivors of this disease, and he looked at me and said: you could be one of them.

This made me think: I’m going to be one of those long-term survivors. I would say the big three things I do for myself are exercise, sleep and diet. Exercise brings blood to the brain and that helps. I always say it also brings the brain into a meditative state. I don’t know if you ever experienced that when you run.

When I first got my diagnosis I didn’t think I needed a support group, but I will admit something: years later, when I joined a monthly support group I noticed how it was both good for me and for others who had just been diagnosed.

You can watch a video about Yaron’s diagnosis here and find out more about Yaron’s story on his website.